Flipped classroom approach to clinical seminar

Image credit: Uuganmn

Image credit: UuganmnThe NCE

The NBCRNA administers the National Certification Exam (NCE) to measure the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary for entry-level nurse anesthesia practitioners. The NCE is a variable-length computerized adaptive test for entry into nurse anesthesia practice.

This test “for entry into nurse anesthesia practice” tests higher order knowledge meaning that simply being able to regurgitate the textbook is not enough. Students must be able to synthesize knowledge and understand it to the degree that they can apply it in clinical situations. This is actually much harder to achieve than you might think. In a traditional didactic classroom based approach this depth of understanding of the material is left to the purview of the student. The problem with this approach is sometimes you don’t know what you don’t know. How can we ensure our students are truly understanding the material and not just regurgitating what was read in the textbook?

For adult learners, I find it works best for the students to use a flipped classroom approach where the students read the material and develop their own understanding of the content before presenting it to the other instructors and students. This method requires the students to read and engage the literature to develop their own knowledge and understanding of the topic. To accomplish this, I use a combination of the Feynman Technique and the socratic method to help develop that understanding.

Richard Feynman was a world renowned theoretical physicist who won the Nobel Prize in 1965. He was brilliant in his own right.

Feynman developed this method for learning and internalizing topics. Now known as the Feynman technique, this simple process has 4 steps:

Step 1 – Study

The first step is a no-brainer. Study the topic in question. We provide our students with a list of topics each semester and when they are due. You have the students start by writing down everything they know about the topic and break the topic down into it’s core components. I find that mindmaps work well for this stage as the students can see how all of the components relate and formulate an understanding of how the components interact. Students already do this to some degree as they are studying, but if not, encourage them to write down everything they know about a topic before actually starting the study process. In the clinical arena, students have already been exposed to these concepts through their didactic education as well as through their patients. If they explore their knowledge before reengaging the content in the textbook they will develop a better appreciation for how important reading the textbook is to their learning. Otherwise rereading the textbook reinforces prior learning and it is all too easy to think that they didn’t really need to read again.

Step 2 – Teach

Once they have studied the topic, it’s time for step 2. They have to teach it to someone else. I encourage students to do this at home as well and not just in the classroom setting. The shared mental model of a doctoral classroom allows us to gloss over lower level concepts that might fundamentally contribute to a misunderstanding of the concept at some level. With the time constraints of a typical didactic lecture this is necessary to some degree, but is avoided in this approach. I recommend that the students try to explain the concept to their spouse, child, or friend that is not in the program.

The person being taught should not just be an active listener, but an active participant. In other words, they should be trying to learn the content. Stopping the student to ask questions and clarify content as they need to understand it. In the flipped classroom approach, this is often up to the instructor to play this part. Have the student explain concepts not only when you detect something is not fully understood, but also when the concept is not explained simply enough. This process can be uncomfortable for all involved and the student often does not like having their train of thought interupted, but this part is crucial for step 3.

I like to use the socratic method here.

Socrates describes himself not as a teacher but as an ignorant inquirer

By asking probing questions, the student has to keep going deeper and deeper into the well of understanding to fully explain the concepts. This process should uncover more weaknesses in their logic and knowledge of the content. If no weaknesses are found then congratulations you are done. If some are found them move on to step 3.

Step 3 – Fill the Gaps

Step 2 should uncover some gaps in the knowledge base. In step 3, the student will start over at Step 1 to add in the elements that they were weak on and turn them into strengths. In the filpped classroom approach, I have an open book and phone-a-friend policy. The student that is presenting has first right to demonstrate their knowledge, but if they need help then one of their classmates can chime in. If nobody can answer the question we go to the book or literature for the answer. For the time restraints of seminar sometimes we will have a few students look up the answer while we move on in the topic. When all else fails, I will give then an answer and have them confirm or refute my answer with evidence from the literature.

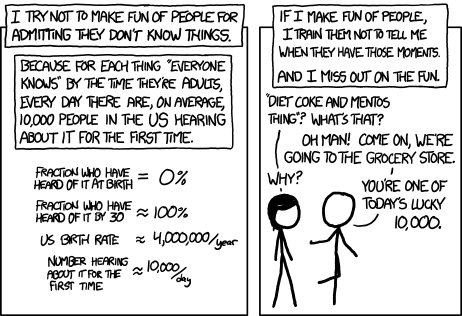

Saying what kind of idiot doesn’t know about the Yellowstone supervolcano is so much more boring than telling someone about the Yellowstone supervolcano for the first time.

Sometimes you are wrong!

None of us are perfect in our understanding and sometimes this process uncovers some weaknesses in your own logic. Don’t be afraid to admit you are wrong when this happens. This sets the expectation of infallibility and discourages open and honest dialog. Sometimes you get a student that just wants to refute everything you say and has this desire to always be right. Try not to take offense when this happens. If you look hard enough in the literature, you can probably find something to refute almost everything you say. Sometimes this ends up being a lecture about interpreting evidence and how 1 article does not make and evidence base. However it goes, if the student had to read 15 articles on a topic just to find 1 that refuted what you said then that student has read 16 articles that they wouldn’t have otherwise.

Encourage students to fact check things you say. You might be right, they might be right, but you’ll both come out better off for it.

Step 4 – Simplify

At this point, it is easy just to say that you are done, but all of this knowledge needs to be synthesized and summarized. If this isn’t done the student might come back to their notes on the topic some months later and study the original(incomplete) notes instead of simplifying the topic and distilling the information down to the essential components. It is still not easier to understand than when they first wrote it. If they truly understand the topic, they will be able to cut away all of the clutter and simplify the topic so that they can explain it to anyone.